U.S. farmers plant approximately 125,000 acres of onions each year and produce about 6.75 billion pounds a year. This includes organic production, but excludes bulb onions for dehydration.

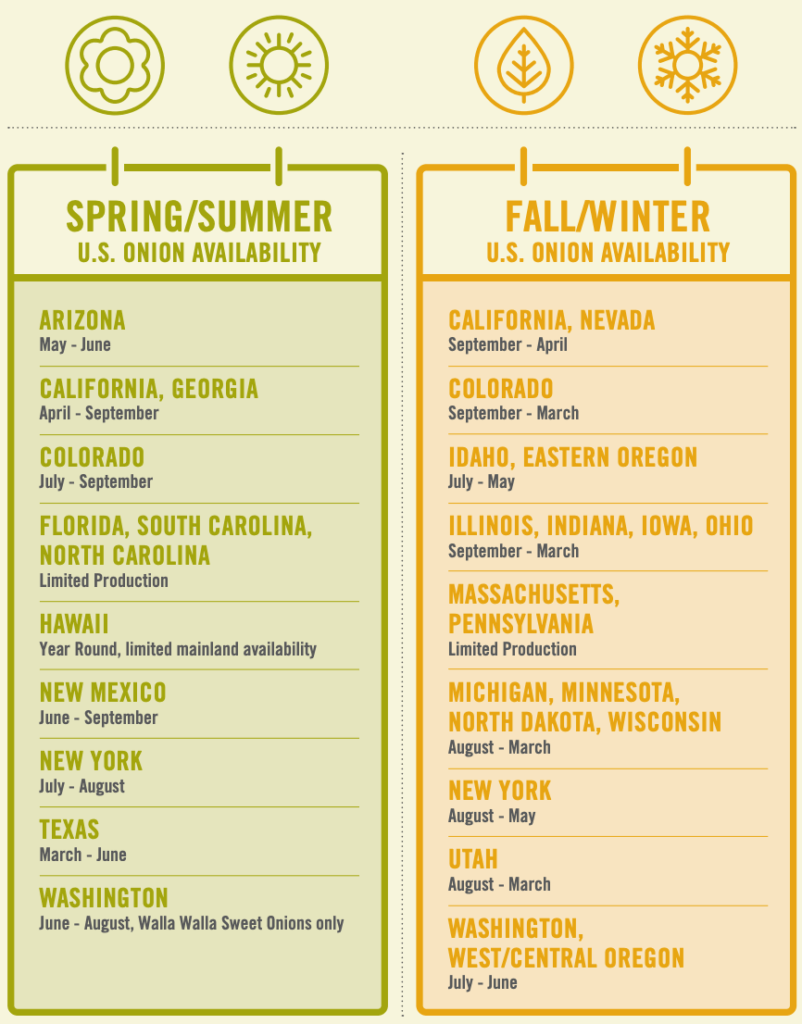

A domestic supply of yellow, red, and white onions is available year-round ranging in size from less than one-inch in diameter to more than 4.5 inches in diameter. Onions from the U.S. can be divided into two categories based on when they are harvested.

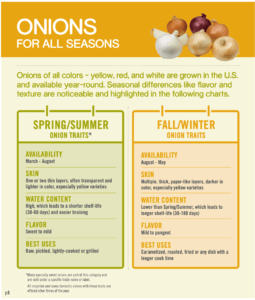

Spring/Summer Onion Traits

Spring/Summer Onion Traits

- Available in yellow, red, and white from March through August.

- Can be identified by their thin, lighter-colored skin.

- Typically higher in water content, which reduces their shelf-life and makes them more susceptible to bruising.

- Range in flavor from sweet to mild.

- Best to use in salads, sandwiches, and fresh, lightly-cooked or grilled dishes.

- Many specialty sweet onions are part of this category and are sold under a specific trade name or label.

- Note: Some domestic and all imported onions with these traits are offered other times of the year.

Fall/Winter Onion Traits

- Available August through April in yellow, red, and white

- Easy to recognize by their multiple layers of thick, darker colored skin

- Commonly lower in water content, they have a longer shelf-life

- Range in flavor from mild to pungent

- Best for savory dishes that require longer cooking times or more flavor

Note: Organic onions are available from several states.

*Producers and some production areas (e.g., South Texas; California Valleys; Vidalia; Georgia; Walla Walla, Washington; New Mexico, etc.) trademark their brands and labels. Individual trade names and private labels are too numerous to mention.

Where Do Onion Varieties Come From?

For centuries, onion (Allium cepa L.) seed has been produced by random crossing among plants by insects such as bees and flies. The result of this open pollination (OP) is that any given onion plant is genetically different from other plants in the population. This high degree of genetic variation results in non-uniformity for important traits such as maturities, disease resistances, bulb shapes, etc.

In the mid-20th century, breeders started to self-pollinate onions to produce more genetically uniform inbred lines. These inbred onions were less vigorous and yielded less than the original OP populations from which they were derived. Fortunately, vigor can be restored by the natural crossing of two inbred lines to produce hybrid onion. Onion hybrids are more uniform for desirable characteristics, show consistently higher yields than OP varieties, and represent 90 to 95% of production in the USA. Both hybrid and OP onions have been improved only by classical plant breeding.

Towards the end of the 20th century, recombinant-DNA technologies were developed that allowed for the isolation of a gene from one organism followed by placement of this gene into another organism. This process is referred to as “transformation” and does not rely on natural crossing between the organisms. The recipient of a gene cloned from another organism is often referred to as “genetically engineered”, “transgenic” or a “genetically modified organism (GMO)”. There are NO genetically engineered, transgenic, or GMO onions in commercial production in the United States.

This statement is an educational resource for information purposes; it is not a position paper of the National Onion Association, National Allium Research Conference, United States Department of Agriculture, or the onion industry.

Written by Michael J. Havey, USDA-ARS and University of Wisconsin-Madison.

Approved for posting by the NOA in July 2015. Revised June 2017.